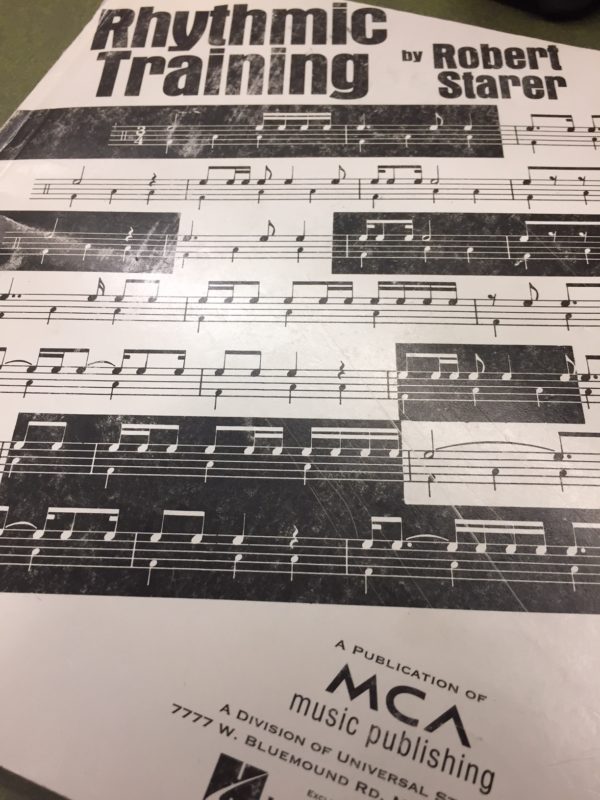

As an undergrad, we used Rhythmic Training by Robert Starer in our theory classes. Honestly, I’m a little fuzzy on which theory classes used it (edited to add: after consulting the label on the back of my book, it was used in MUSI 1111, which corresponds to Aural Skills I at Kennesaw State University). I kept almost all my textbooks (with the exception of my least-favorite sight singing book!), and as I moved further along in my applied teaching, reached for this one when I had students who could benefit from some isolated rhythm practice.

As an undergrad, we used Rhythmic Training by Robert Starer in our theory classes. Honestly, I’m a little fuzzy on which theory classes used it (edited to add: after consulting the label on the back of my book, it was used in MUSI 1111, which corresponds to Aural Skills I at Kennesaw State University). I kept almost all my textbooks (with the exception of my least-favorite sight singing book!), and as I moved further along in my applied teaching, reached for this one when I had students who could benefit from some isolated rhythm practice.

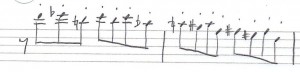

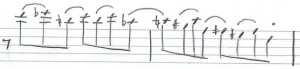

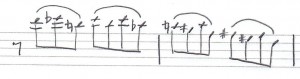

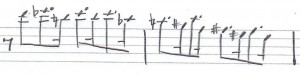

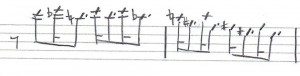

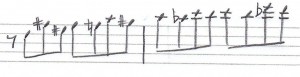

The book begins with what students frequently think are insultingly-easy exercises: counting quarter, half, dotted-half, and whole notes. The layout is such that the steady pulse is printed at the bottom of the staff, and the rhythm under consideration is printed at the top of the staff. There are a few pages of “Preliminary Exercises” (the “easy” ones), and then it moves into twelve chapters. I caution students about taking these exercises for granted based on the beginning material because they increase in difficulty at a swift pace. After treating both common and lesser-seen time signatures, there is a section in Chapter 1 on changing meters. Chapter 2 introduces subdivision in a variety of time signatures. Chapters 3 and 4 introduce more complex subdivisions. By the time we reach Chapter 5, the exercises mix the types of subdivisions (eighth notes, triplets, sixteenths, etc.). Increasingly small subdivisions is the subject through Chapter 9. Chapter 10 changes the rate of pulse; Chapter 11 is a review, and Chapter 12 pits two rhythms against each other.

Often I will use this book with students with limited experience with applied lessons. Sometimes students are very comfortable playing in a large ensemble where there is a conductor and relatively steady pace. When this pulse has to come from the student himself, problems can present themselves.

Practically, I will usually include one or two pages per week. The student is free to work through these however he or she would like, but we always “perform” them the same way in lessons. If they feel comfortable with the material, I turn on a metronome click and off they go, playing the rhythm printed at the top of the staff. If they aren’t comfortable with the material, I have them talk through, analyze, and clap the rhythm in question. We continue to work on smaller and smaller sections to zoom in on the trouble spots. Once we practice it (much in the same way we would practice an excerpt from their etudes or repertoire), they play through it on the flute.

In my experience, working through these exercises results in significant improvement. Even working through approximately half of the book sets student flutists up for success in most rhythms they will encounter in the standard repertoire. Lesson time is at a premium (especially when underclassmen have a 30-minute lesson each week) but this book is worth fitting in. The fundamental skills gleaned from it pay off dividends when learning the vast majority of our repertoire.