Do you need a flute fingering chart? I tend to get a lot of questions about how to play certain notes, or where to find a reliable source of finding how to play certain notes. A fingering chart lists every (well, for the most part) note that we can play on the flute, and it tells you which keys to press down and which keys to leave open to create the particular note you’re trying to play.

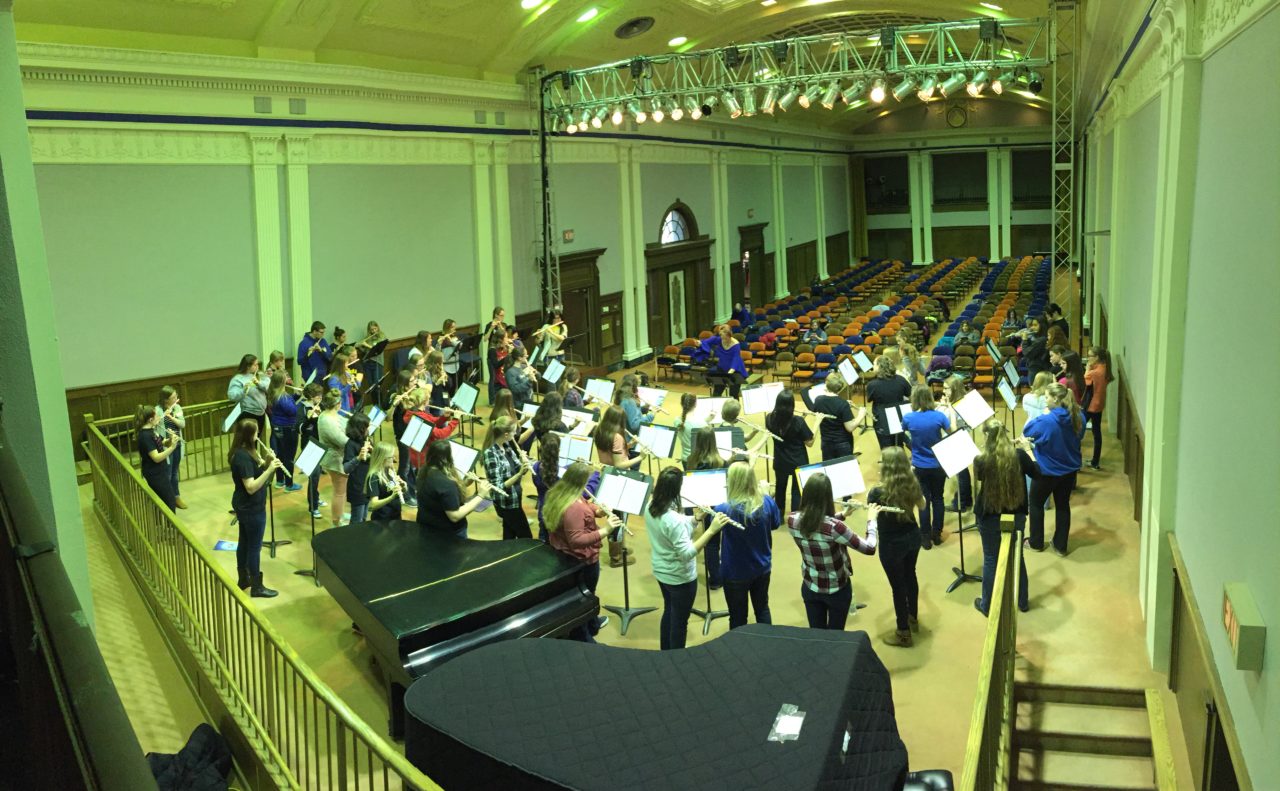

Here are some options when you’re learning flute:

1. If you’re currently playing out of a flute method book, there should be a flute fingering chart included in the front or the back of the book. Lately, I have preferred using the Flute 101 series.

2. If you would like a smaller, more portable flute fingering chart, they make laminated ones like this one. If you use a flute carrying case (other than the hard plastic or wood case your flute fits in), it can usually be tucked into there, or it will fit into your band folder, flute bag, or bookbag. Don’t force it into your flute case! Anything other than the actual flute can bend or break fragile flute parts!

3. If you want a website, I always recommend The Woodwind Fingering Guide to my students. It lists the most common notes we play, as well as the extreme upper register. It covers all the woodwind instruments, so be sure to share it with your friends!

4. If you prefer a visual demonstration, check out videos on my TikTok or YouTube. I have a bunch of videos made for many of the flute notes we play; if it isn’t up there, send me an email and I’ll get it made for you!

If you have another fingering chart you happen to love, please let me know! I’m always adding to my teaching material arsenal and would love to see your favorites.

If you’re looking for flute lessons, I’d love to work with you! I teach online and you can book a time slot with me here!

*Some of the links contained in this post may be affiliate links. This means — at no cost to you — I may earn a commission if you make a purchase. That helps to support this site. Thanks!